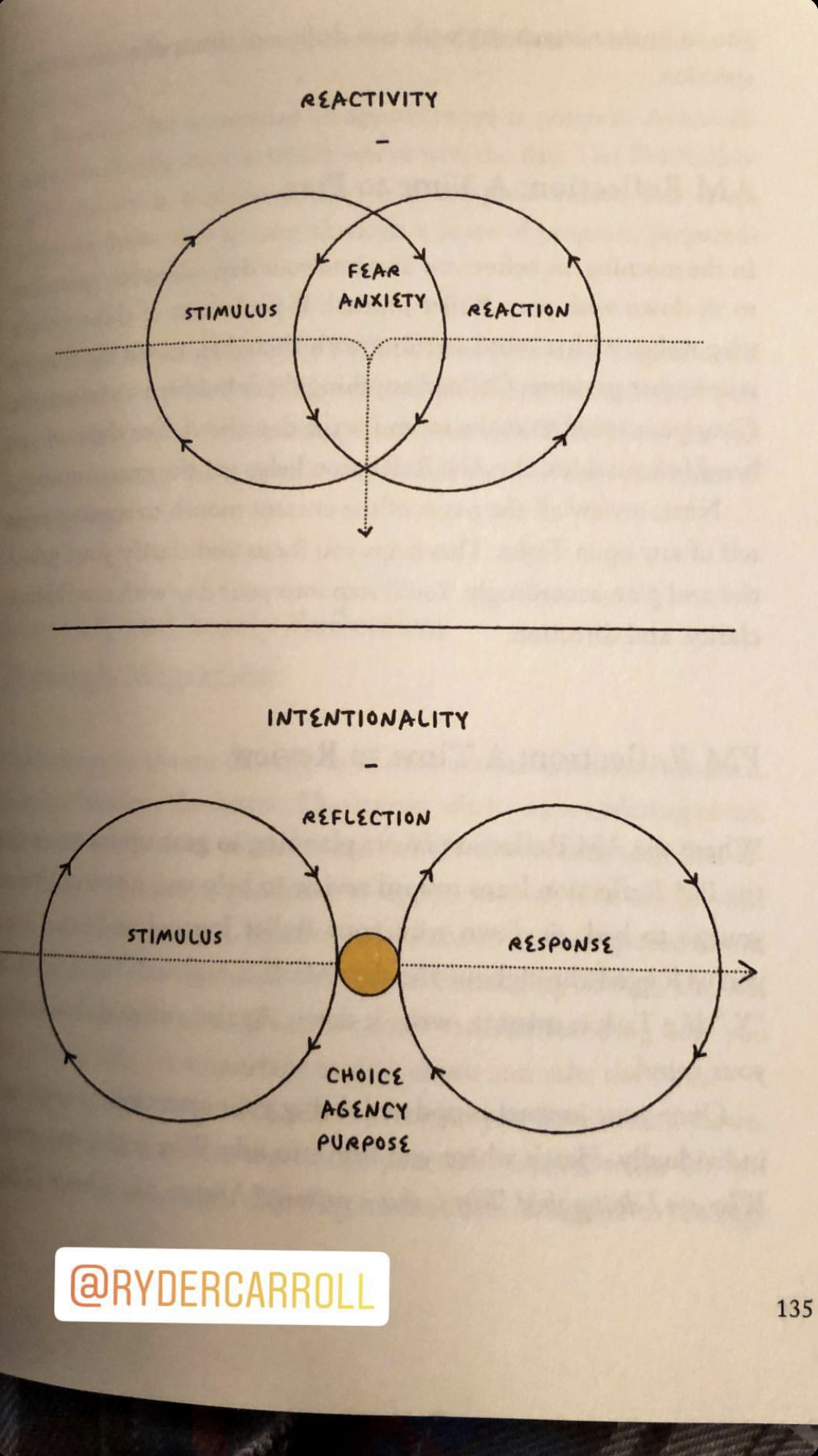

Several longitudinal studies have confirmed the expected association between high cardiovascular response to stressors and higher incidence of hypertension, but others have found this relationship to be modest or absent after partialing out higher resting BP, which is associated with both high stress response and later hypertension. High heart rate, blood pressure, cardiac output, and vascular resistance responses to stressors have been shown to be relatively stable characteristics of certain individual across challenges and over time intervals from a few months to as long as 10 years. The reactivity hypothesis has generated considerable research and much debate since the 1970s. In the latter case, it is suggested that transitory episodes of elevated adrenergic and cardiovascular activity, if evoked on a frequent basis by stressors in an individual’s environment at home or work, may eventually induce secondary changes leading to resetting of homeostatic mechanisms to a higher level of blood pressure (BP) maintained even in the resting state, and to structural changes in the heart and vessels. High stress response may be simply a marker of increased cardiovascular risk, or it may play a more direct role. The classic reactivity hypothesis in its most general form posits that individuals who are high reactors to behavioral challenges or stressors will over time be more likely to develop elevated blood pressure and hypertensive heart disease (characterized by left ventricular remodeling and hypertrophy) and/or coronary heart disease (characterized by stenosis in coronary vessels, which can lead to myocardial infarction). Who is a high reactor to this challenge and who is a low reactor? Can we use the magnitude of reactivity or change in physiological response to reveal an underlying response that is excessively great or small, and therefore indicates dysregulation in a key physiological system? Can we show that someone who is a high reactor to one challenge will be a high reactor to others, and will high or low responses to laboratory stressors reflect the relative responses to natural life demands?

The primary interest in human research on cardiovascular reactivity is actually on the study of individual differences. Then the mobilization increases cardiac work and stresses the vasculature with no apparent benefit. In modern industrialized societies, however, the remnants of this response pattern (minus much of the dilation of blood vessels) are frequently evoked during cognitive and emotional stressors where physical activity does not increase. Also described as the fight-or-flight response, the hemodynamic adjustments were adaptively designed to mobilize the cardiovascular system to provide extra oxygenated blood flow to working muscles before and during vigorous activity. Historically, the best-recognized pattern of cardiovascular responses has been labeled the defense reaction, an increase in heart rate and blood pressure and a decrease in vasoconstriction seen in cats during hypothalamic stimulation that also engaged motor responses mimicking those occurring when the animal was faced with a predator. The hypothalamus plays a major role in the integration of cardiovascular responses and thus is always part of the initiation, maintenance, and post task recovery of cardiovascular responses to behavioral events. The regulatory systems that allow transitory increases in blood pressure, heart rate, cardiac output, and/or vasoconstriction include efferent activity via sympathetic and parasympathetic nerves to the heart and blood vessels adrenocortical and adrenomedullary hormones such as epinephrine, norepinephrine, and Cortisol neuropeptides such as oxytocin, vasopressin, and atrial natriuretic peptide and other substances with endocrine activity. Others involve dealing with complex interpersonal interactions based on prior learning and experience, like job interviews or driving a car in heavy traffic.

For the cardiovascular system, some challenges are as simple and routine as changing from supine to standing posture. Although homeostasis is a common characteristic of the underlying physiology of humans and most other life forms, our regulatory systems possess the adaptive capacity to mount relatively dramatic temporary changes to respond to and even anticipate challenges.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)